Guest Blog: Rustling in the Gauze – Nabokov and Fighting

Lillian Wilkie is an artist, educator and bookseller based in London. Her work incorporates photography, sculpture and installation with writing and quiet performance. Her current research explores the life of sculptor, wrestler and opera singer Sam Rabin.

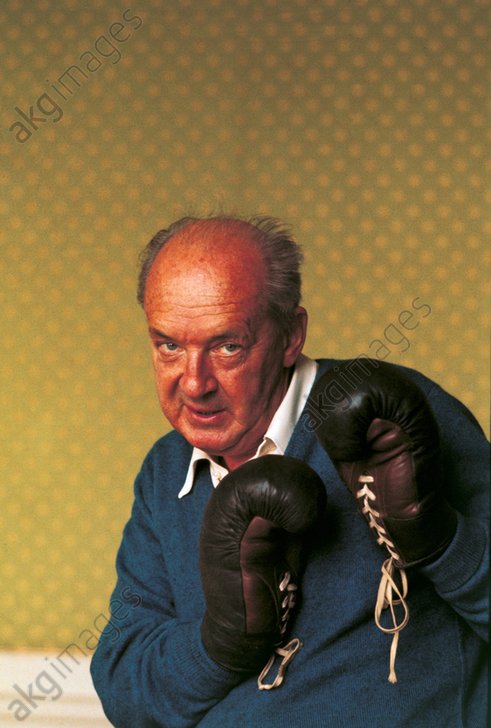

For her blog post, Lilian chose one photograph from the archive and wrote her response to it below:

© akg-images / Mondadori Portfolio / Giuseppe Pino

On my bedroom wall is a photograph, printed on newsprint now creased and yellowed, of Vladimir Nabokov, butterfly hunting one afternoon in Ithaca, New York. Captured at the cool finish of a decisive lunge forward, his net splayed flat against the forest path, Nabokov seems hopeful. The scene holds its breath; the only movement a slight ripple in the cottonwoods, and the click of a shutter. All eyes are on the folds of gauze anchored to the path, searching for the lightest quiver of the insect, proof that the thrust was exact.

Perhaps it was of this moment that Nabokov wrote:

A blow of the net – and a loud rustle in the gauze

O, yellow demon how you tremble!1

A blow of the net, a swipe through the air, a hook and then a jab at the startled quarry; from some distance an observer might perceive a man engaged in a bizarre sparring match with an imaginary opponent, like children often do when left alone and to their own devices. Those tender, winged demons were worthy adversaries to Nabokov, who was both captivated by the gorgeous intricacy of the hundreds of lepidopteran specimens he helped to categorise throughout his lifetime, and also a great lover of contest. The “quick flurries” of the pursuit, its “wary circlings, its duelling antitheses”2, indubitably call to mind another of Nabokov’s passions – boxing.

“Everything in the world plays: the blood in the veins of a lover, the sun on the water, and the musician on a violin,” wrote Nabokov in the opening lines of “Breitensträter–Paolino”, a paper he first presented in December 1925 to his literary circle in Berlin. Later published in the Latvian émigré journal Slovo and thus one of Nabokov’s earliest published short stories, “Breitensträter–Paolino” recounted a tremendously popular heavyweight boxing match that had taken place that same December at the Sportpalast in Berlin. In reverent tones, its Nabokovian narrator describes the crowd’s tremulous anticipation of the fight, the revelation of the challenger’s gladiatorial physique at the drop of a “splendid robe”, the might of the opening assault, the juicy slaps of the gloves, and the early spatters of blood. Adopting the knowing diction of a sports hack, Nabokov’s prose is undercut with a vigorous insistence on the beauty of the bout, rendering the great, hulking bodies as dancers within a shimmering ring, encircled by a rapturous crowd. Whilst the narrator cannot be precisely identified with Nabokov, the writer had a great fondness for the sport. He recounts in his memoirs that a “wonderful rubbery Frenchman, Monsieur Loustatot”3 would often visit the family home in St Petersburg, sparring with his father and giving lessons to the young Vladimir. He took up boxing again at Cambridge (where he initially read zoology), and continued to organise bouts with friends, mostly fellow writers, on his transfer to Berlin.

On more than one occasion in “Breitensträter–Paolino” Nabokov nods to the recognised rapport between literary heavyweights and their pugilistic counterparts, acknowledging the atavistic romanticisation of the sport in the writing of Byron, Bernard Shaw and Conan Doyle, which would be further articulated later in the twentieth century by Hammett, Hemingway and Mailer, amongst others. What Pierce Egan called “the science of sweet bruising” was, for Nabokov, a deeply remarkable form of play; a kind of play that transcended the apparently innocuous passing of time and truly embraced what he saw as inherent deep in the heart of all types of play – violence. The boxing match satisfied not just man’s innate attraction to physical encounter, but also the voyeuristic urge to watch, resulting in an experience unparalleled across the gamut of endorsed and legal spectacle.

That the sedentary writer might experience affinity with the boxer is not impossible to understand, but easy to mock, as many did when Hemingway claimed in a letter to Josephine Herbst, “My writing is nothing, my boxing is everything.” But Nabokov, unlike Hemingway, never crowed of his achievements within the ring, fighting fiercer with his words. For he recognised that the boxing match encapsulated the very human characteristics that stir the spirit of a great writer: blind courage, vulnerability, endurance and grief. Early in “Breitensträter–Paolino” Nabokov compares the speckling of blood on a referee’s white shirt to the leaked ink from a fountain pen – blood and ink, two means of expression, aggressively wrought.

The world of boxing, of course, has its special partiality for language and narrative. Integral in the build-up to a championship match is the unburying of the hatchet, the bellicose media appearances and the lyrical trash-talk, exemplified best by Muhammad Ali. Ali knew that the first punches were thrown well before the tolling of the referee’s bell, and inspired by the adversarial character archetypes of professional wrestling he spun long and colourful yarns of glory guaranteed, in an unbroken pre-hip hop patter reminiscent of 1960’s radio DJs. In evoking the wider world of the arts and literature in his auto-encomia, Ali sublimated the impending fight into a dance under lights, echoing Nabokov’s prose in “Breitensträter–Paolino” and its metaphorical flourishes (“Breitensträter lay twisted like a pretzel.”)

Ali also said a thing or two about butterflies.

Everything in Nabokov’s world plays. The play of sunlight on water, the song of a musician; Humbert’s chessboard, Quilty’s tennis and Ada’s Scrabble; games of style, language, and metaphor; puzzles, false scents and decoys; mind games, mean, manipulative games, games of hide and seek, and the play of past torments on the mind. “Breitensträter–Paolino” is ultimately a discourse not on boxing but on the art of play, devoted to formalising through language not just the sheer violence of the bout but the absolute apotheosis of competition itself. Nabokov, forced out of his home after the Bolshevik revolution and eventually into an exile that would last his whole life, squarely rejected the Communist emphasis on homogeneity and unity, convinced that the strongest must be allowed to exploit the weaknesses of others, and the potential for competition maintained. Embodied in every leap through those woods and fields of Ithaca, net outstretched, was the essence of “Breitensträter–Paolino”; the splendour of contest in which there can only be one winner.

© Lillian Wilkie 2015

- Nabokov, V., “On Butterflies”, in Nabokov, V.; Boyd, B. (Editor); Pyle, RM. (Editor); Nabokov, D. (Translator), Nabokov’s Butterflies, London, Penguin, 2001

- Karshan, T., “Vladimir Nabokov’s ringside vision of art and life”, The Times Literary Supplement, London, 1st August 2012

- Nabokov, V., Speak, Memory: An Autobiography Revisited, London, Vintage, 1989