Hitting the Mark…

Behind the scenes of the documentation department

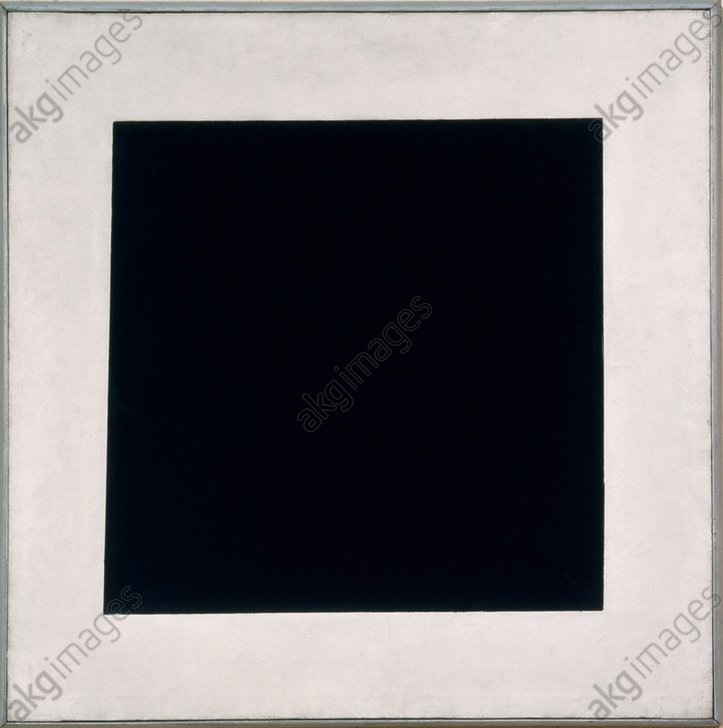

At “The Last Futurist Exhibition 0,10” in St. Petersburg in late 1915, an artist hung his painting so that it touched both walls close to the ceiling in the corner of the room, like a Russian icon. It was moments away of becoming his most notable work.

Even at the time, it was enthusiastically received by contemporary artists, and made a splash well beyond the Russian border. The painting marks a milestone in art history, and has become an icon of abstract art.

What’s the title of this key work of art? Here’s a hint: “(…) to paint. Preferably the Big Bang. The sensation of non-representation. Back to the point. Or rather – the square. A square invokes many things or everything; four corners. Four seasons. Four directions. The figure of the cross. The earthly figure. The figure of life itself, (…) The unframed icon of my time. Said the artist and leaves it with the white background. The square. Blackness. Whiteness. Nothing – outside of sensation. (…)”

(from: Elisabeth Koeppe, Gut geraten!, Berlin 2014, p. 126).

Anniversary Thoughts

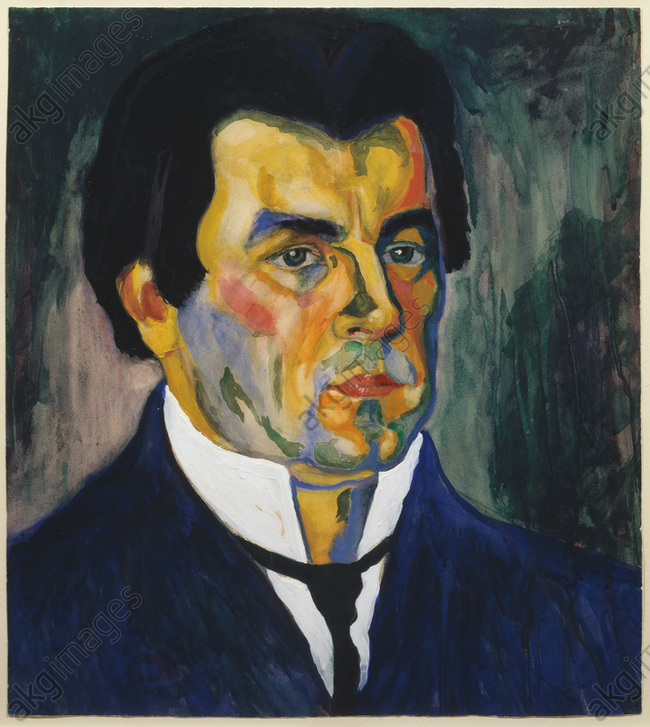

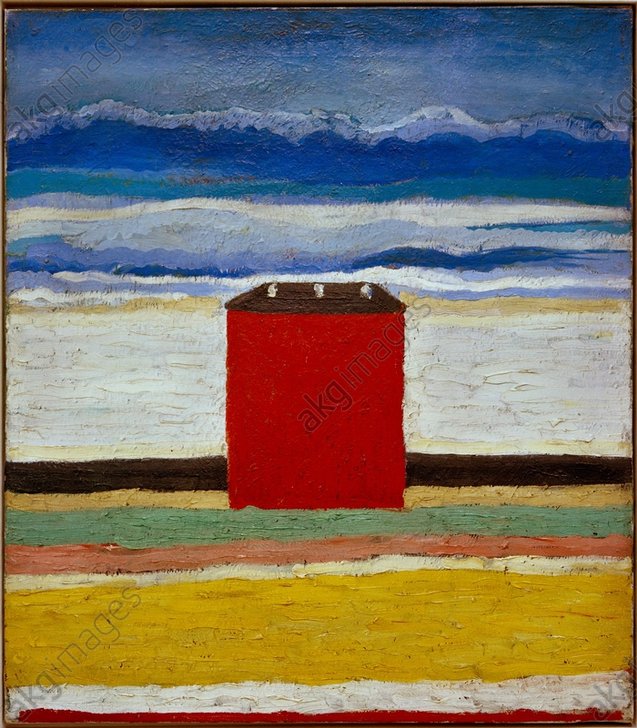

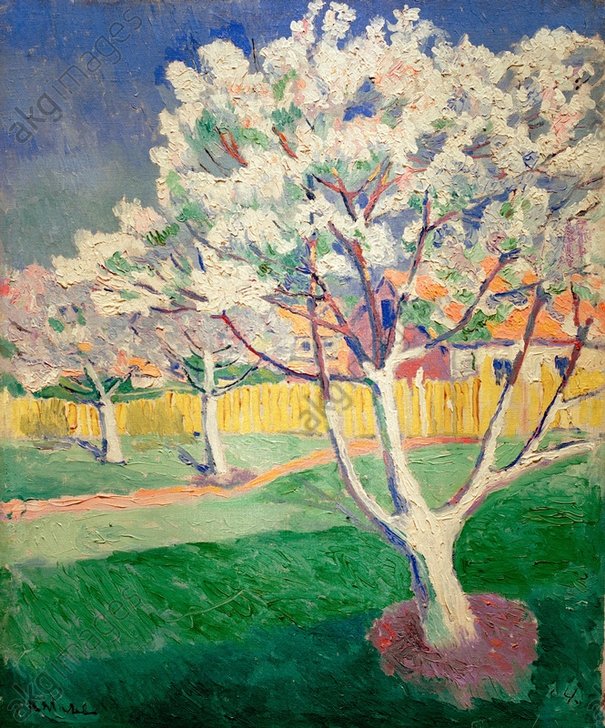

The anniversary of an artist’s birthday is always a fine opportunity to reconsider his life and work. That’s how we felt in the Picture Research and Documentation departments when it came to the birthday of Kazimir Malevich, and together we created an album of his impressive oeuvre. Browse the Malevich album >>>

An anniversary album naturally calls for some introductory words.

While preparing a translation from German to English, a colleague at akg-images London brought to our attention that two different birth years for Malevich seemed to be given in biographies.

How could this be? That’s where our detective work began.

Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNB): 1878 (also 1879) … Ah, interesting!

Library of Congress (LOC): 1878

St. Petersburg, Ermitage: 1878

Russisches Künstlerlexikon: 1878

Getty Research: 1878

wikipedia.de: 1878

wikipedia.en: 1879

wikipedia.fr: 1879

Tate Modern: 1879

Allgemeines Künstlerlexikon (AKL): 1878

What’s a researcher to do?

Since the Tate Modern explicitly points to to the English Wikipedia entry, I return to it in detail:

There is a link to a document dated 2012 from the Central Archive of Kiev, quoting the church register of the Catholic Cathedral in Kiev. A Russian speaker translates for me: it unquestionably states “11 February 1879” (o.s. 23 February 1879). Why then the alternative date of 1878?

Digging deeper: I discover that Malevich himself dictated a few autobiographical notes to his wife Natalia in 1928 or 1929, which were found in her estate and published posthumously. There he states he was born on 11 February 1878 in Kiev (see Irina Vakar, Malevich’s Student Years in Moscow: Facts and Fiction in: Malevich. Artist and Theoretician. Moscow-Paris, 1990, p. 28).

Strange that Malevich should be mistaken about his own year of birth. Did he wish to appear older to his third wife Natalia Manchenko (1902-1990)? Pure speculation!

Discrepancies are also found in his notes about his education (as above, see: Irina Vakar, p. 28 f.). It is possible that dates in general didn’t hold much significance to him.

Notably, the revised birth year 1879 was pointed out in 2002 by Bulgarian-French art historian Andréi Nakov and published in the context of his comprehensive catalogue of Malevich’s works. However, few other authors appear to have taken heed of his findings (see https://andrei-nakov.org/)!

When Russian art historians claimed to have discovered Malevich’s correct birth year as 1879 in a lecture at Centre Pompidou in April 2017, Andréi Nakov wrote an article titled „Une soi-disant «découverte» d’une nouvelle date de naissance de Malewicz“. His conclusion hits the mark with the vaguely resigned phrasing: „Ainsi va le monde de la récupération“, meaning: that’s the way it is with the – literal – “recovery” of historic facts (see here).

There is no logical explanation. One cannot consider such selective methods as solid academic research.

So I began to correct all our birth dates for Malevich from 1878 to 1879, in order that our picture researchers in Berlin, London and Paris would be able to write a consistent introductory text for the Malevich 140th anniversary album.

The discrepancy was originally brought to our attention by our London colleague Anya Prosvetova. Our thanks goes to her for her diligence!

(Christiane Saumweber; translation Julia Neumayer)