A Declaration of Love

One of the many perks of being a Picture Researcher for an archive as varied as akg-images is being able to time-travel on a daily basis. Sitting at my desk in London I have experienced many adventures over the years:

in the 1930s I endured the cold of the Baltic and was welcomed by the warmth of its inhabitants. I learned what it really meant to be thirsty when I crossed the Sahara by car in the sweltering heat and felt my heart race as I watched snake farmers extract serum for medicinal purposes from the fangs of Brazilian cobras. In 1943 I laughed and cried simultaneously at the sight of children playing in the bombed out streets of Marseille, wondering how they keep their spirits up in a city that is nothing but a mere skeleton. I saw that a mannequin in Chanel robes can be just as elegant as an African chief in worn out dusty brogues. I spent much of the 1950s strolling through a decadent night-time Paris, watching lovers embrace on boulevards glistening from the rain; I listened to the sound of the gravel under my feet when I explored the paths along a Vietnamese rice field, seeing the women harvest the grains. In the 1960s I heard the rustling sounds of a man plaiting rushes for baskets in Central Africa and I walked with gold seekers in Bolivia; I tasted the flavours of Indian, Indonesian, Nigerian and Hawaiian food and I fell asleep to the sound of an Arabian desert at night.

And I have fallen in love with a man. A man who has not only seen all these places in his lifetime, but documented them in such a way that it now requires very little effort to picture yourself in the sceneries. His way of seeing, his patience, humbleness and his determination and dedication have created one of the most exceptional and significant collections of our archive.

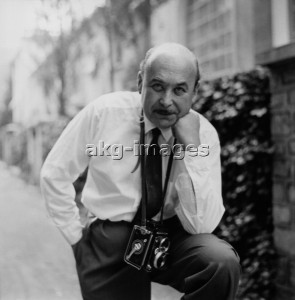

It is ten years this month that Paul Almasy, photographer, political scientist, journalist, globetrotter, tutor, seeker and silent observer, embarked on his final journey on 23 September 2003, aged 97.

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

He spent over five decades travelling the globe so that at the time of his death, there was only a single country he never visited: Inner Mongolia. He was fluent in Hungarian, German, Italian, French, Spanish and English which allowed him to directly communicate with many communities without the help and distraction of a translator. His passport would have been a colourful array of stamps and permissions, gathered, as he reached even the most remote corners of this planet to document the hardship, suffering and daily routines of human lives.

Photo: akg-images

Looking through Paul Almasy’s archive one soon begins to feel that he was everywhere at the same time. This impression is justified when we bear in mind that he spent 9-10 months travelling, followed by 2-3 months archiving his images, writing reports and planning the next journey. A lifetime spent out of a suitcase, accompanied by his loyal Rollei capturing, but never sensationalising the beauty and anguish of life. Always the distant observer, never an intruder, his way of working was influenced by his studies of political science: he remained ever the diplomat, never compromising raw reality for vain aesthetics.

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

His black and white archive, now exclusively represented and maintained by akg-images, contains approximately 120,000 images. This may not sound like a colossal amount when we compare it to today’s constant stream of images, overwhelming us in their numbers, yet easily archived and stored within minutes. Every single photograph by Paul Almasy was developed and printed by hand, the film cut into individual negatives, stored in small paper pouches, dated and numbered and systematically archived in boxes sorted by countries.

Many treasures are yet to be discovered in these boxes. Standing out from the material that is scanned and archived in our digital searchable database, are Paul Almasy’s photographs of children. During his work with UNICEF, UNESCO and WHO he documented the cause and prevention of malnutrition, illnesses and the struggle for education in Asian, South American and African countries. Always keen to capture the natural behaviour of his subjects, Paul Almasy remains the silent observer in the background that portrays life in all its facets: the painful and the joyous ones.

Brassaï, Robert Capa, André Kertész and Moholy-Nagy were his fellow countrymen, yet Almasy’s work was never as famous as that of his contemporaries. Maybe this is because he was not like some other photographers of his time, who valued composition and stricter rules in photo reportage. Capa famously said “If your photographs aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough” [1]. Paul Almasy preferred to keep his distance so not to disturb the natural flow of events and emotions, yet his images are never detached or aloof, they are not spectacular but are always informative and quietly poignant.

He particularly enjoyed photographing children as he felt their honesty, spontaneity and innocence mirrored the purity of their soul before we learn to conceal our emotions and become more guarded and skeptical. In Paul Almasy’s images we see children of all ages playing, reading, sleeping and laughing but also working, suffering and dying.

I now invite you to be a time-traveller with me as you take a stroll down the paths of your own childhood memories, inspired by some of the photographs that I selected from this vast historical archive. Maybe seeing a piece of the world captured by Paul Almasy will make you understand why I have fallen in love with this wonderful man and his truthful vision of the human condition.

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Photo: akg-images / Paul Almasy

Footnote:

[1] http://blogs.reuters.com/photographers-blog/2007/11/15/if-your-photographs-arent-good-enough-youre-not-close-enough [Accessed 20.09.2013].