Goya’s ‘The Disaster’s of War’

Goya’s The Disaster’s of War (Los Desastres de la Guerra), 1810-1820

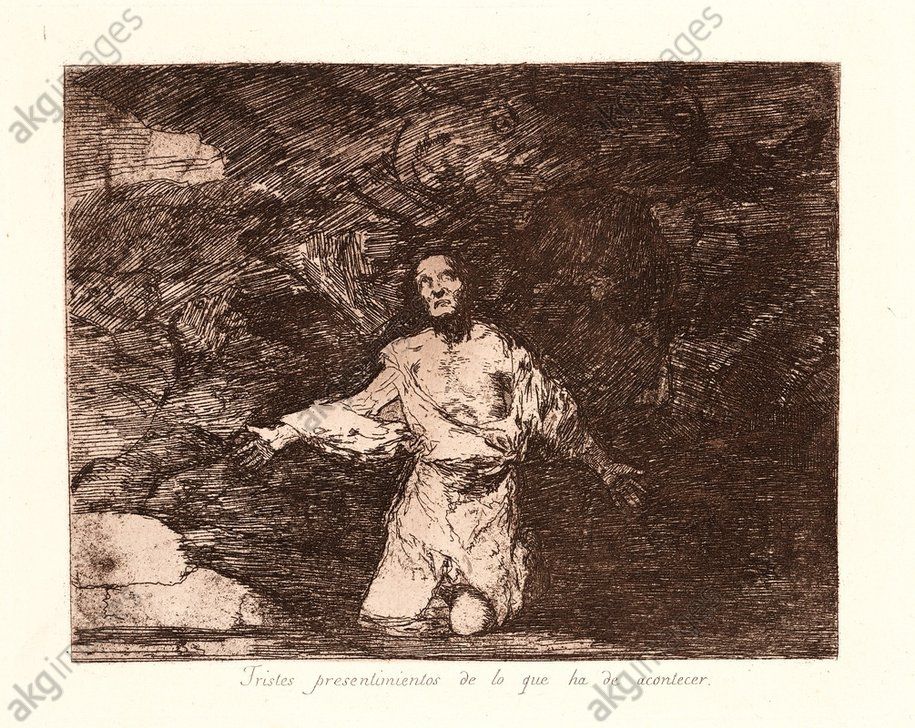

Between 1810 and 1820, the Spanish painter and print maker Fransisco Goya (1746–1828) produced a series of around 80 etchings he was to call The Disasters of War (Los Desastres de la Guerra). Arguably his darkest works, they were created in response to the war between France and Spain between 1808 and 1814, known as the Peninsular War. In 1808 French troops invaded Spain in an attempt by France’s Napoleon Bonaparte to install his brother Joseph Boneparte as the King of Spain. These etchings show scenes from the Spanish struggle against the French army after the invasion, and explore the horrifying consequences of guerilla warfare, and the famine that followed it.

This type of visual record of war was perhaps the first of its kind. Previously art had been used as a tool for propaganda – glorying one or the other with heroic depictions of battles. In this un-commissioned series, Goya attempted to record the unfolding horror and its aftermath as he experienced it. In that way we get a sense of truth and authenticity about the images which remains as impactful and relevant today as it did then. Neither side – French or Spanish – are glorified, and as a result these etchings were not published until more than 40 years after Goya’s death.

The series can be roughly grouped in to three sections:

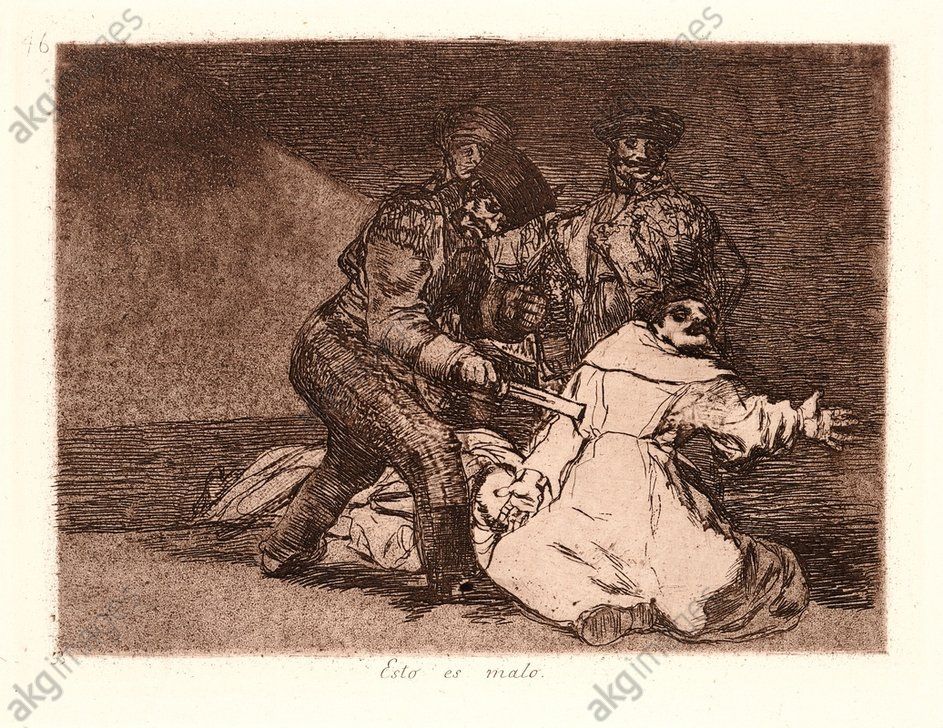

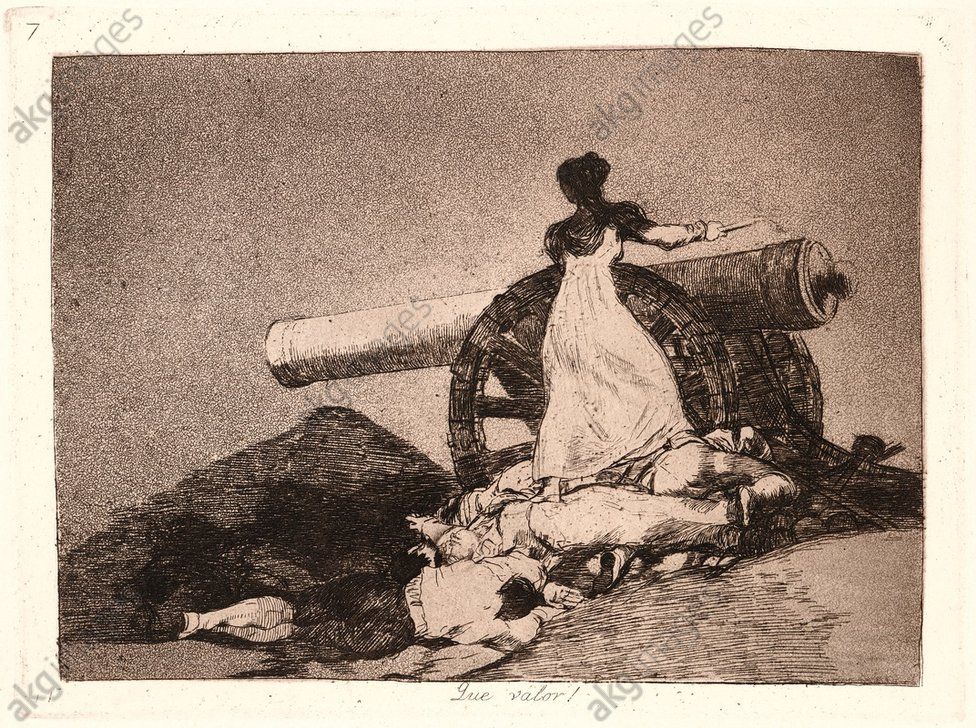

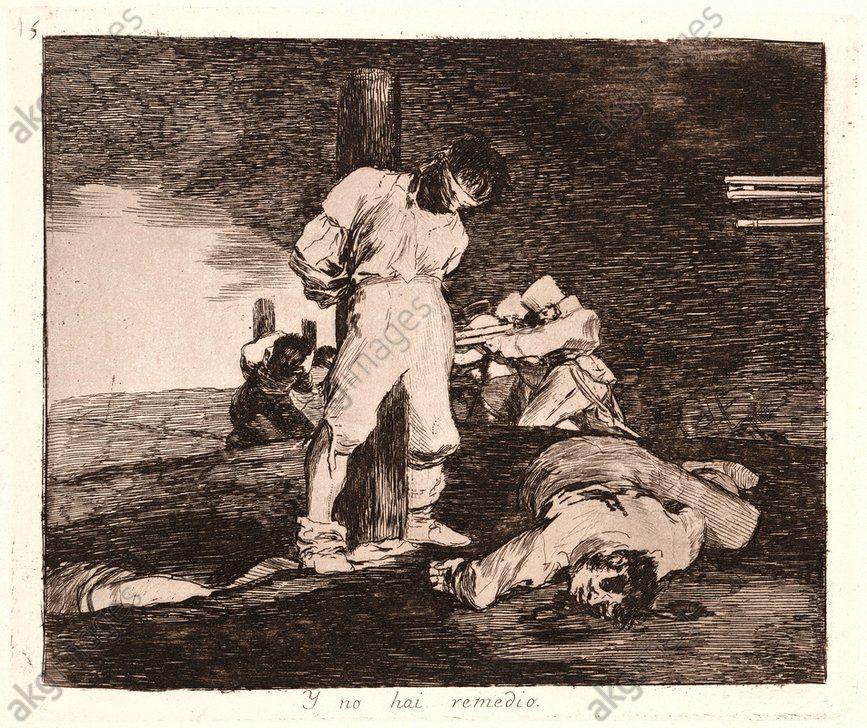

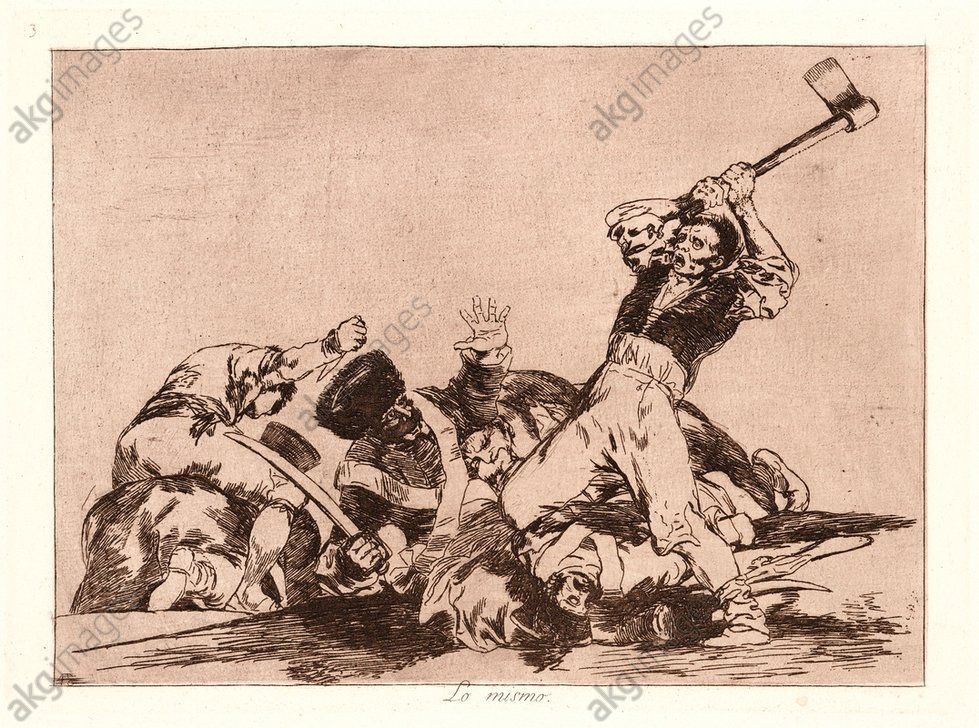

Plates 1 to 47 consist mainly of realistic depictions of the horrors of the war fought against the French.

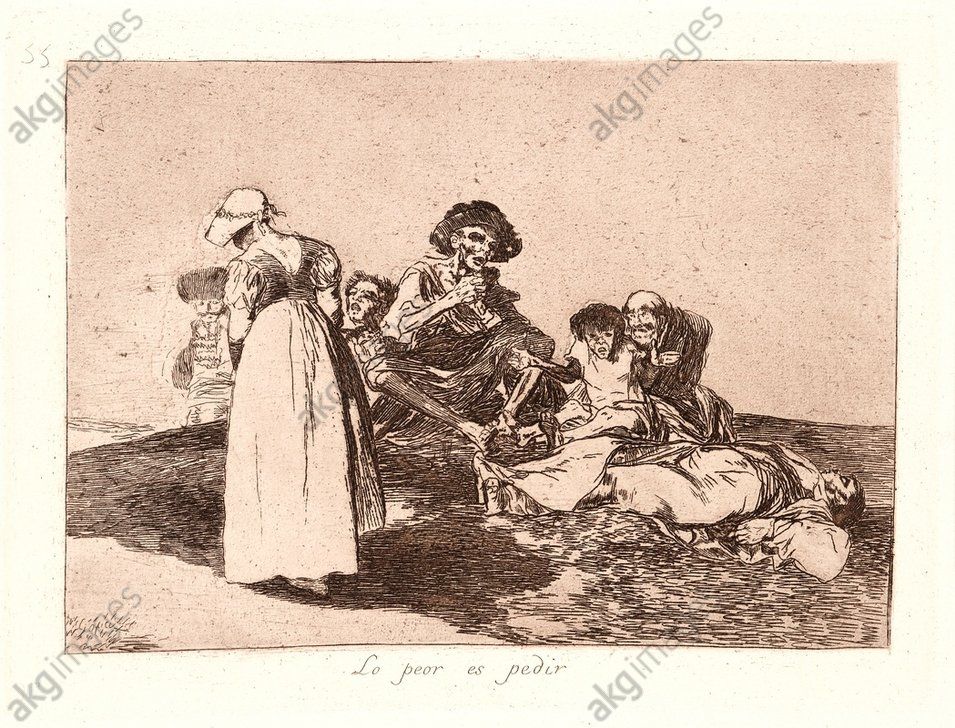

Plates 48 to 64, detail the effects of the famine which ravaged Madrid from August 1811 until after Wellington’s armies liberated the city in August 1812.

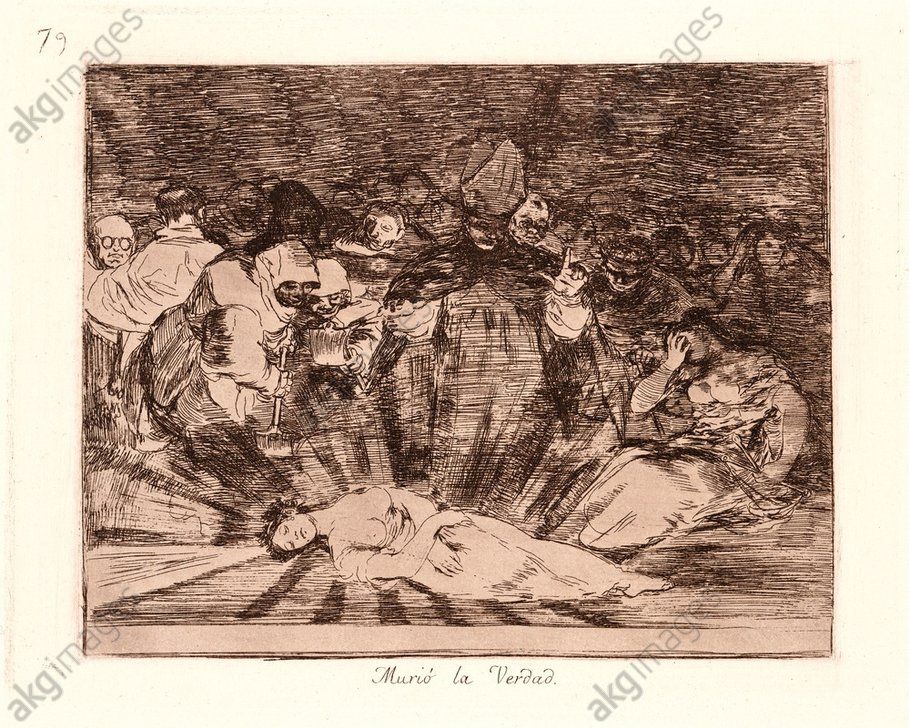

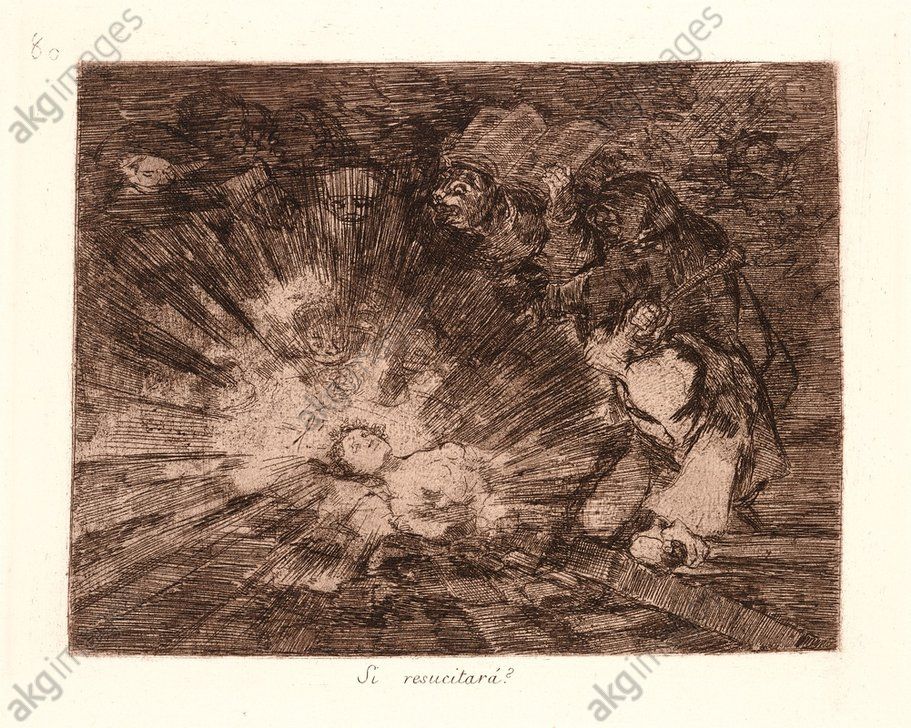

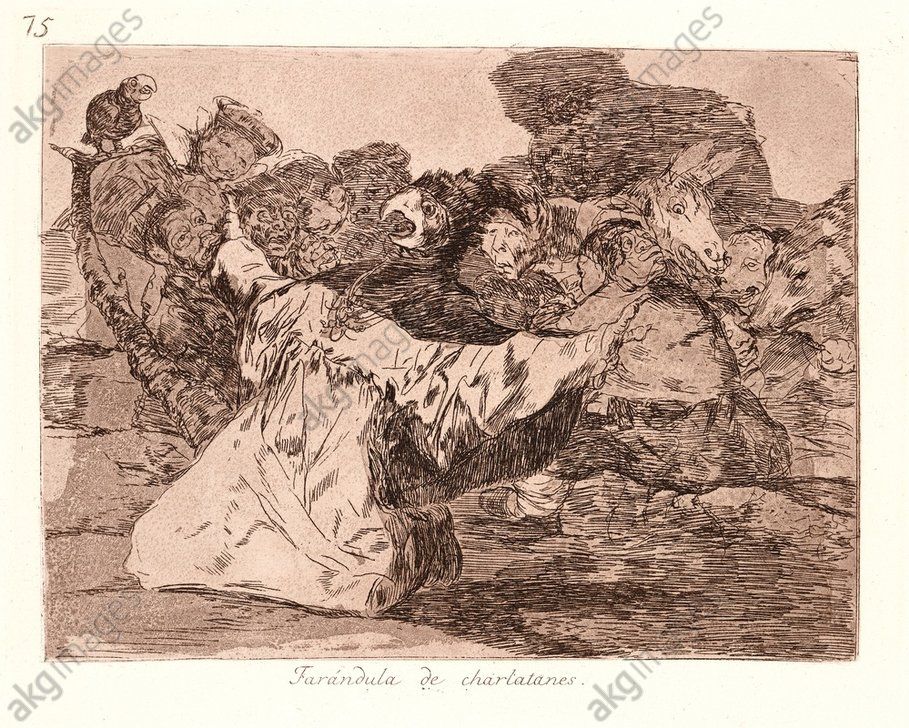

Plates 65 to 80 were named “caprichos enfáticos” (“emphatic caprices”) in the original series title. Completed between 1813 and 1820 and spanning Ferdinand VII’s fall and return to power, they consist of allegorical scenes that critique post-war Spanish politics, including the Inquisition and the then common judicial practice of torture.

Some in the series etchings Goya shows scenes of specific events that happened during the war. For example plate 7 titled What Courage! (Que Valor!) shows the heroism of a woman named Augustina Zaragoza (also known as Augustina de Aragon) during the 1807 Napoleonic siege of Saragossa. Legend has it that when the Spanish militia had suffered too many deaths and injuries to fight the attacking French troops, Augustina managed to repel them single-handedly by firing a cannon on the advancing French soldiers.

Many of the other etchings show scenes of brutality that were inflicted on the Spanish people by the French army. Etchings such as And There’s No Help for It (Y No Hay Remedio), plate 15 in the series, shows Spanish prisoners being excectuted by French firing squads. Plate 13 – Bitter to Be Present (Amarga Presencia) – is one of the many etchings showing scenes of assualt on Spanish women by French soldiers – rape was common during the war.

While Goya depicts the Spanish people most often as victims of French brutality, he also shows the power war has to dehumanise everyone involved. In prints like And they are like wild beasts (plate 5), the aggressors are Spanish women, fiercely protecting themselves and their children with spears and stones against the French army. In Plate 3 – Lo mismo (The same) – Spanish men are shown maiming French soldiers with a axes and knives. These depictions show the beastial quality that is brought out when people are pushed to the extreme, however Goya is ultimately on the side of the common people who are more often the victims of conflict.

Real scorn is reserved for those in charge, and the tyranny of monarchy (both French and Spanish), as well as the clergy also come under attack. As a liberal, Goya was dismayed at the increasingly repressive political enviroment in Spain that followed the war once the French were ousted. Etchings such as Esto es lo peor! (This is the worst!), plate 74, we see a wolf writing orders to a line of poor and hungry people, assisted by a member of the clergy. Plate 75 Charlatans’ Show (Farándula de Charlatanes) shows a priest with a parrot’s head performing before an audience of donkeys and monkeys.

Even in less repressive times etchings like these would have been highly controversial. Goya was still working as a painter for the Spanish court at that time, so unsurprisingly this series remained unpublished during his lifetime. They were only published in 1863, more than 40 years after Goya’s death.

With titles such as Why? and What more can be done, Goya seems to be pleading with us the viewer and humanity as a whole to give answers. As these scenes have repeated themselves time and time again through out history, ultimately we are all complicit in this misery and only we have the power to change things.

Click here to see the full series.