A personal view of the First World War: Photo albums

From the collections of the Archiv für Kunst und Geschichte (akg-images) – Part I

The collections held by the Archiv für Kunst und Geschichte – today better known as akg-images – contain an extensive store of historic photo albums. These are amongst the great treasures of the archive and were collected over the nearly 70 years of our existence as a photo agency. There are over 600 albums in the archive, including family albums, travel albums and company records covering the past 150 years, as well as personal German photo albums from the First World War. The centenary of the outbreak of the war allows us an opportunity to look through these albums and, through their photographs, to remember the experiences and suffering of people during those war years.

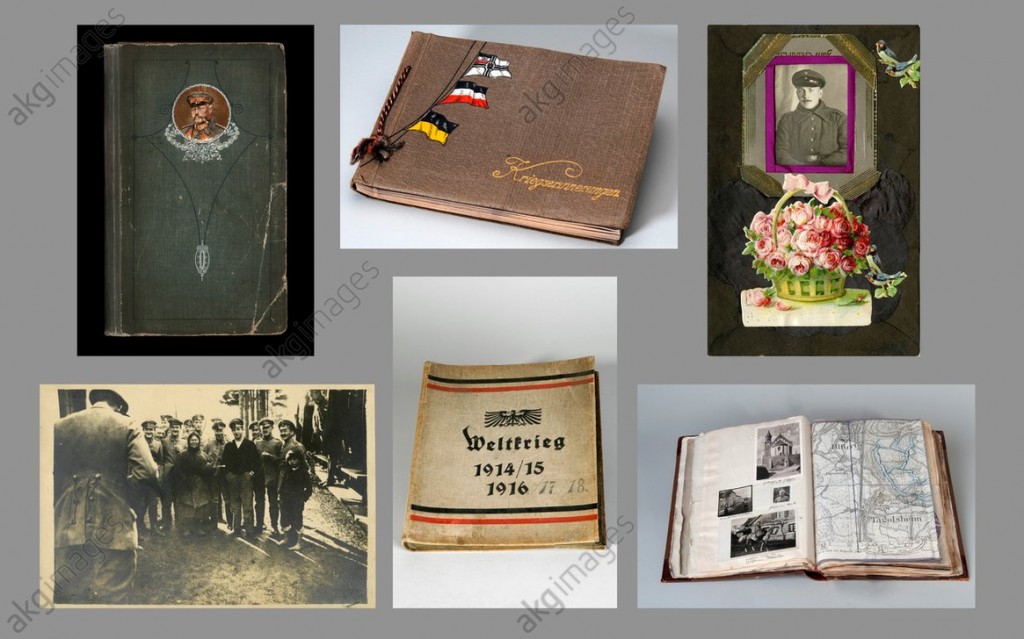

The photo albums carry names like “Memories of War” or simply “Album”, others show the Iron Cross, the portrait of Hindenburg or the title “World War 1914/1915/1916”, with the years 1917 and 1918 added in by hand underneath, a reminder that everyone had expected a short war or a rapid victory. “You’ll all be home by Christmas”: those words from the Kaiser in August 1914 rang in everyone’s ears, but this optimism soon turned into a significant sense of disillusionment.

100 years later, there is a glut of images covering the period of the First World War. Although photography was still a young medium, the war coincided with its first blossoming. It pays to look carefully at these images and to differentiate between them. Are they official images, propaganda designed to write history? Or are they documentary images, or even private views by amateur photographers, looking at the events of the war without any disguises or embellishment? In many personal photo albums,for example in the extensive album of the lawyer and later publisher Dr Hanns Krach, we find this particular view of history, where often only a split second separated the living from the dead. Others are clearly meant to be documentary, they give an official account of the action, for example the Rottländer album entitled “History of Reinforcement Battalion 161”, a battalion stationed in Lümschweiler (Alsace) in 1917. Frequently the albums look like collages, so in addition to the amateur photography, they contain postcards, sketches, comments on the images or reports and news articles. In many of them there’s curiosity about other people and regions, almost a touristy feel, often side by side with photographs of the day-to-day war and its all-destructive power.

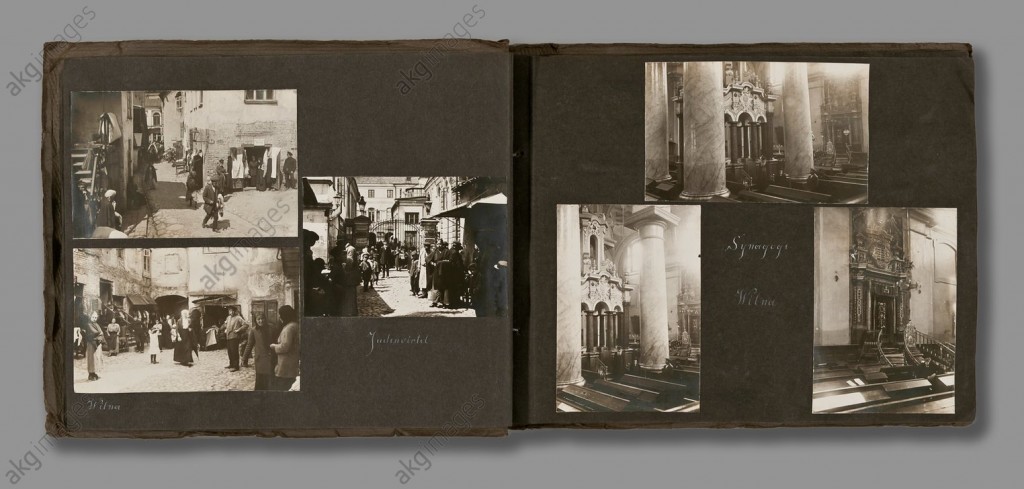

One album by an unknown amateur photographer takes us to the Eastern Front, to Poland and Lithuania. This photographer was interested in the life and culture of the people in this foreign country occupied by German troops. We see everyday Jewish life in “Vilna” (now Vilnius, capital of Lithuania) in the streets and markets, the interactions of the Jewish population and German soldiers. You can sense the photographer’s cultural and historical interest in the era, because alongside pictures of the “German Church”, the “St Michael Church” and the “St Bernard Church”, there are also images inside the Great “Synagogue of Vilna”: in its centre the elevated platform, the bema, surrounded by four massive Tuscan columns, and a shot of the Torah shrine. During the Second World War this synagogue, the largest in Lithuania, was largely destroyed by Nazi occupiers and no longer exists. In 1916 there were over 74,000 Jews in Vilnius, accounting for around 40% of the population. These amateur photographs illustrate a curiosity and normality in dealing with other cultures that, 25 years later in the very same place and in a similar situation, became unthinkable. The First World War was about conquest and subjugation, but it was not about conquest and annihalation. Of the 80,000 Jews in Vilnius in 1939 only a few thousand survived the Holocaust. Looking at these pictures from the First World War, you have also to think about the horrors of the Second World War as well.

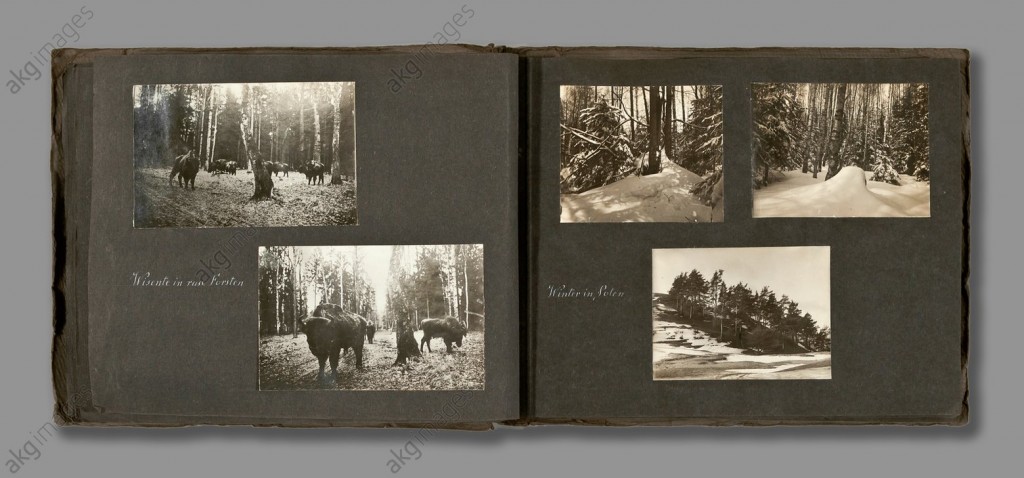

In this album, there are also pictures of a wonderfully unspoilt landscape with captions like “Winter in Poland” and “Bison in a Russian forest”. They reveal a sensitive eye for the beauty of nature, with bison roamed in birch forests, a sight which would have made the hearts of hunters beat faster. At that time bison were only to be found in the East, in the rest of Europe they had long since been hunted to extinction. Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg took a short break from battle to hunt the beasts himself in January 1916. Even Prince Leopold of Bavaria, Commander of the 9th Army, had already proudly hunted and killed his first bison in the conquered land of the Tsar on 19 September 1915. A pleasant diversion for him, but life for ordinary soldiers on both sides of the Front was not quite as entertaining. Often, as with my great-grandfather Friedrich Karl Engelmann, the German Empire and its desire to conquer all led to loss of life. In his last letter to his wife written on 19 May 1915 at the Eastern Front, my great-grandfather wrote, “We live like wild animals, we mustn’t show our heads….” A few weeks later he was badly wounded in a skirmish at the Dubissa, fell into Russian captivity and went missing – a fate he shared with hundreds of thousands of soldiers.

Next follow photographs from a sporting event which seem almost grotesque given the context. The pictures show an embarrassing level of precision to ensure that competitors’ hands are placed correctly on the starting line. None other than Prince Oskar of Prussia (1888-1958) witnessed this “Turf Sports Festival of the Imperial Vilna Governorate on the Vilna Antokol Racetrack”, now a suburb of Vilnius. The images show that organised physical exercise and sports was seen as of great importance not only before but also during the First World War, offering a great opportunity for the company commander, assault troops and for everyone else who wished to prove themselves heroes to prove their prowess.

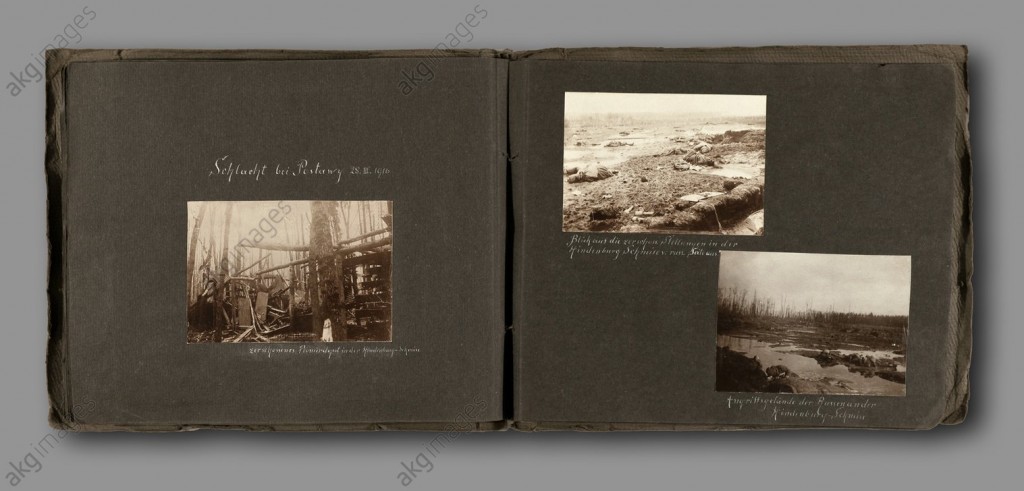

On the very next page we see death and devastation, photographs of the Battle of Postawy, today in Belarus. We are assaulted with the horror of war in these images. Countless fallen soldiers lie in the mud, the endless misery and suffering clearly visible. There are photos taken after the collapse of the Russian spring offensive on the Northern Front. The offensive began on 18 March 1916 and over 140,000 Russian soldiers lost their lives. The images carry captions like, “View of the destroyed positions along the Hindeburg Line seen from the Russian side.” Not only Russian and German soldiers lost their lives here, nature itself was destroyed and desolated. These are apocalyptic images, later depicted by Otto Dix in his paintings, for example in “The Trench”, a work deemed by the Nazis to be so detramental to wartime morale that it was burned and survives today only in reproductions. At the end of this personal photo album, we look into the faces of Russian war prisoners, some defiant and questioning, their fates uncertain. The following photograph “Behind the position of Inf. Regt. 131.” also shows the dead on the German side.

At the end of 1916 the German Supreme Army Command, understanding the importance of images in warfare, created the “BUFA”, an office designed to control the way images and film of the war were seen and used. The importance of photography in this respect had long been recognised, but it was difficult to suppress the use of amateur photography in the First World War: it was already a mass phenomenon.

Many of the personal photo albums now archived at akg-images reflect not only the euphoria at the beginning of the First World War but also the disillusionment of the soldiers as the war progressed. The albums also question the very meaning of this war, the tremendous sacrifices demanded of the soldiers and the civilian population, the enormous technological advancements which facilitated millions of deaths and which led literally thousands of survivors into nothingness. At the end of the war, many veterans searched for a way back to an older military structure which, for the Weimar Republic, would have fatal consquences.

Active and open opponents of war like Otto Dix, Käthe Kollwitz and Ernst Toller, or Ernst Friedrich who in 1923 founded the “Anti-War Museum” in Berlin, were very few. Many of the surviving soldiers sorted through their photographs, labelled them carefully and stuck them into albums so they could document their war experiences and explain them to them family and friends. Your own personal memories of this “seminal catastrophe” of the 20th Century were accorded a permanent place in a private photo album.

There was no official site for remembrance for the Germans. While war museums were built in England and France, the extensive plans for a new “imperial war museum” in Berlin were shelved in late 1918. The High Command had worked intensively since 1916 on the implementation of the new museum and had already spent a million Reichsmarks, so plans were well advanced by 1918.

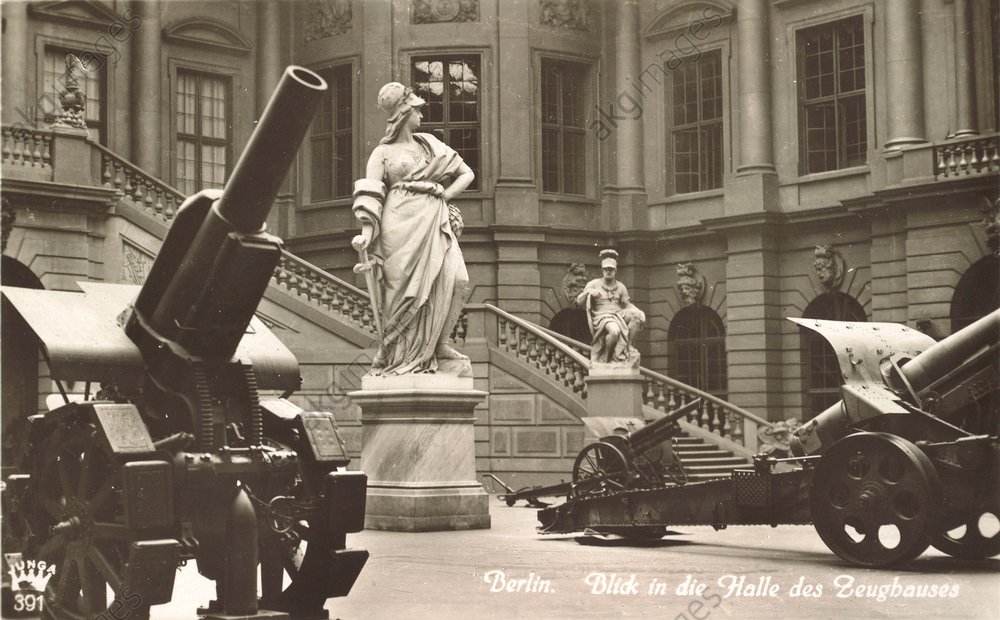

The war museum was supposed to be housed in the Zeughaus in Berlin, the old Arsenal with its Prussian Ruhmeshalle. The Zeughaus had been used during the war to exhibit booty, but it was only towards the end of the Weimar Republic that the first exhibition on the Great War was staged here due to stipulations set down in the Treaty of Versailles. From 1933 onwards, the Nazis mercilessly exploited the Zeughaus for their own war propaganda to reassess the national trauma of the Great War. By romanticising the weapons and heroics of the First World War, the old myth that Germany was “undefeated on the battlefield” could be popularised once more.