Albrecht Dürer, Renaissance man

Ask someone to name a great Renaissance artist, and the answers you’ll hear are most likely Italian: Michelangelo, Raphael, Da Vinci, Botticelli. I have never understood quite why Albrecht Dürer doesn’t make the list of well-known Renaissance artists more often. Perhaps it is because, here in the UK at least, very few of his autograph paintings are in British collections. Many of his masterpieces, including the oft-parodied “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse” are prints, too sensitive to light to be on show permanently so the casual museum visitor is unlikely to see the extraordinary detail Dürer was able to achieve in woodcuts and engravings.

Dürer was a true Renaissance man: a polymath who wrote theoretical works on measurement and human proportions; an entrepreneur who went to court to prevent the sale of fake prints bearing a counterfeit monogram; a devout Christian who remained a Catholic throughout his life but who was affected by the writings of his contemporary Martin Luther.

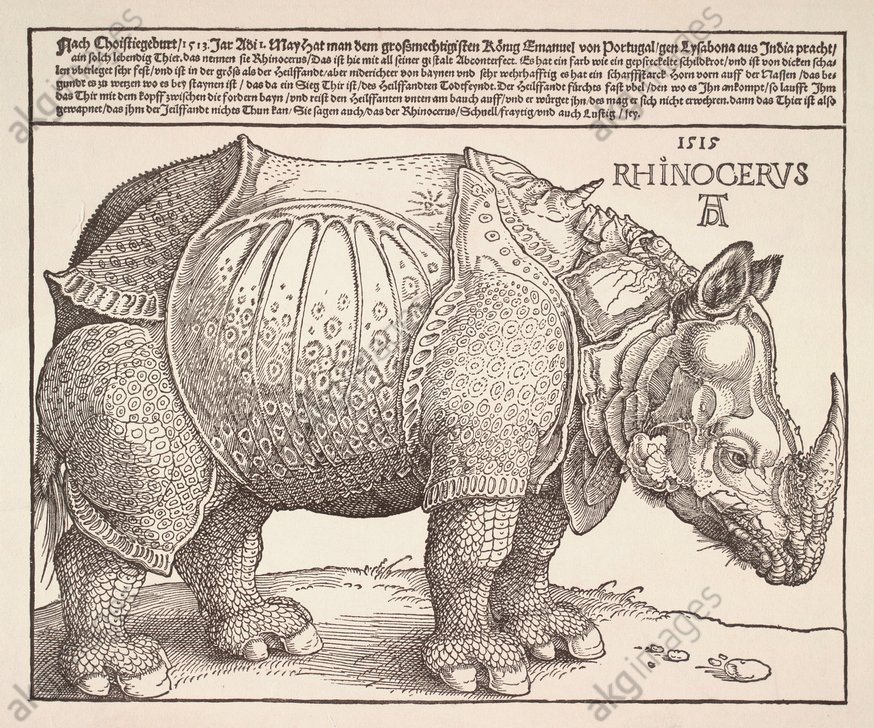

Although he was born and died in Nuremberg, Dürer was fascinated with the world, travelling twice to Italy where he was heavily influenced by Venetian painters and, in particular, their use of rich colour. Dürer was also intrigued by the exotic. His sketchbook from a trip to the Netherlands later in his life includes silverpoint drawings of animals in the zoological garden in Brussels. One of Dürer’s most famous prints depicts an Indian rhinoceros intended as a gift to Pope Leo X from the Portuguese King Manuel I. The poor rhino never reached the Pope, however, drowning in a shipwreck off the coast of Italy, and Dürer himself never actually saw the animal, basing his woodcut on a sketch by another artist and a description of the beast. On display at the British Museum’s upcoming exhibition, Germany: memories of a nation, is an 18th-century Meissen porcelain sculpture of a rhino. Two hundred years since Dürer’s print, and despite the fact that rhinoceroses had since reached Europe, Dürer’s depiction of the rhino is so striking that it was still being used as the reference for the Meissen artisans.

Dürer was also the master of the self-portrait, documenting the changes to his face and body throughout his life. Perhaps his most famous self-portrait, painted when he was 28 years old, is luxurious in its detailed depiction of Dürer’s lionine hair and fur coat. The similarity of Dürer’s self-portrait to paintings of Christ as ‘Salvator Mundi’ is at once obvious and unexplained and continues, over 500 years after its creation, to be the subject of debate amongst art critics. So if you’re ever asked to name a favourite artist, think of Dürer, staring directly out of the wood panel at the viewer, and add his name to the list of the Renaissance greats.

I have created an album of some of Dürer’s great masterpieces, as well as some personal favourites, which you can view over on the akg-images website.