I am not a robot

On Sunday afternoon I found myself surrounded by children at a showing of Martin Scorsese’s latest movie, Hugo. The film is so packed full of wonderful ideas it’s hard to know where to start: it’s a 3D children’s movie that starts off as a tale of a young orphan boy hiding in the walls of a Parisian railway station and then takes a turn and becomes a film about film, most specifically about the early development of cinema.

On Sunday afternoon I found myself surrounded by children at a showing of Martin Scorsese’s latest movie, Hugo. The film is so packed full of wonderful ideas it’s hard to know where to start: it’s a 3D children’s movie that starts off as a tale of a young orphan boy hiding in the walls of a Parisian railway station and then takes a turn and becomes a film about film, most specifically about the early development of cinema.

It was a plot twist I wasn’t expecting: suddenly footage of Harold Lloyd, Louise Brooks and Charlie Chaplin appeared on screen as the two young leads discovered more about the beginnings of film. When a clip of my personal hero Buster Keaton in The General appeared on screen I admit to having a tear in my eye.

The movie is interested in mechanics and machinery: Hugo’s father is a watchmaker; Papa Georges makes and mends toys; Hugo himself oils and winds countless clocks in the railway station; a professor of cinema hand-cranks an early projector. At the beginning of the film, Paris is laid out almost like the workings of a clock, and Hugo explains at one point that he loves machines because no part in a machine is unnecessary, every little cog and spring is needed. If Paris – and by extension the world – is a machine of which he is part, then he is necessary, even if he is alone.

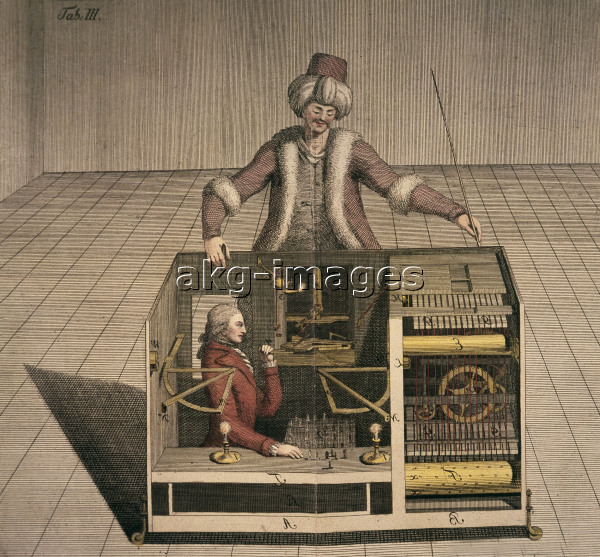

Much of the plot hinges around a mysterious automaton repaired first by Hugo’s father and then by Hugo. The craze for automata seems to have really kicked off in the 18th Century, judging by the images we have in the archive of the chess-playing Mechanical Turk and Marie Antoinette’s mechanical musician. Some of the automata were frauds, of course, with real people hiding in or under them, controlling the action, but many others were feats of early computer technology, writing, drawing, playing music. Our fascination for robots that can act and think like humans continued, though The Tales of Hoffmann to Metropolis to, yes, Bobby the, er, cigarette vending machine.

We’re still obsessed with automata today, except we don’t necessarily expect them to look like Robby the Robot in Forbidden Planet. In an article for the Guardian about his new television series Black Mirror, Charlie Brooker recently admitted to his first ‘unironic conversation with a machine’, speaking to Siri on his iPhone:

“Today it’s Siri. Tomorrow it’ll be a talking car. The day after that I’ll be trading banter with a wisecracking smoothie carton. By the time I’m 70 I’ll be holding heartbreaking conversations with synthesised imitations of people I once knew who have subsequently died. Maybe I’ll hear their voices in my head. Maybe that’s how it’ll be.”

Speaking with Siri is an odd experience, especially in the UK where Siri shares the voice of the voiceover man from The Weakest Link. And it really is speaking with Siri rather than at Siri. We are reaching the point where we can have relatively complex interactions with computers. How long, as Charlie Brooker writes, will it be before we hear voices directly transmitted into our head?

I found the automaton in Hugo a beautiful but utterly creepy machine. Perhaps, as it was a Scorsese movie, I was expecting it to be a malevolent force (or, as it reminded me so much of Chucky, possessed by a malevolent force). Of course it wasn’t and – spoiler alert! – the film ends with a close-up of the automaton’s face. It was interesting to gauge the opinions of the children in the audience, all under ten and digital natives. Not one of them seemed fazed or scared by the creepy wind-up doll; Sacha Baron Cohen’s station inspector was much scarier to them. It seems like the future’s robotic, and the future generation is entirely comfortable with that!