Jacques Louis David – Propaganda Genius?

At university I studied mainly French 18th and early 19th century art and Jacques Louis David obviously featured quite strongly. By the time it came to doing my MA in the Art of the French Revolution, I was totally immersed in French history painting. There are very few of those on view in London and most of the large David paintings are in the Louvre in Paris. We were only a small group and so we had spend some time in Paris and Versailles as well as going to the Museum of the French Revolution in Vizille near the French Alps. The museum there is a whole different story and will need its own future blog!

Back to Jacques Louis David. We had seen and discussed most of his large history paintings from the late 1780s such as “The Oath of the Horatii” from 1784, “The Lictors bring Brutus the Bodies of his Dead Sons” from 1789 and “The Intervention of the Sabine Women” from 1799, all in the same room at the Louvre.

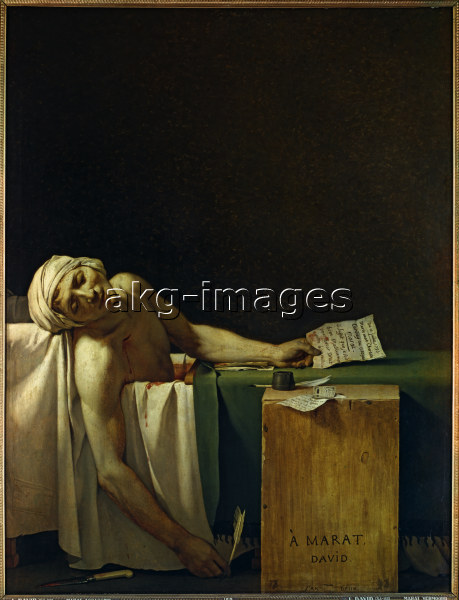

The one major painting from the Revolutionary Period that isn’t in Paris but in Brussels is his “Death of Marat” from 1793. David went into exile to Brussels after the fall of Napoleon and it is here that he died on 29 December 1825.

I had never been to Brussels and in the pre Eurostar days had no really easy way of getting there short of flying. On one of my trips home I managed to persuade my sister to drive with me to Brussels for the day, look at the painting, have some food and turn round. I am so grateful to her to this day – it was a miserable journey, raining constantly, we were in a 2CV and my sister really wasn’t that interested in seeing the painting. Still, it was an unforgettable day and one that we will both remember if for different reasons!

I have always found the “Death of Marat” a fascinating painting – like most of David’s work during this time period it has a very strong political message and in this case even shows the artist’s own political convictions very clearly.

Jean-Paul Marat was a radical journalist and politician, a defender of the sans-culottes and close to Robespierre and Danton – the three of them were for a while the most powerful men in Revolutionary France. Marat ran a paper called L’Ami du Peuple (Friend of the People) in which he published lists of so-called enemies of the people, without much regard as to their guilt or innocence. By all accounts he wasn’t a handsome man, contemporaries commented on his toad-like appearance mainly caused by a chronic skin disease which he could only alleviate by sitting in a bath tub, the same kind that we can see in David’s painting.

Charlotte Corday, a young woman from Caen and a Girondin sympathiser came to see Marat on July 13 1793 under the pretext of wanting to supply him with more names of enemies of the people. She stabbed Marat in the chest and was guillotined for her crime on 17 July 1793. The background story is important to the understanding of David’s painting, especially as contemporary viewers would have been familiar with those details.

The first impression you get is one of an almost empty canvas, the top half of the painting shows nothing much except for an eerie light, the source of which we can’t quite make out. One of the main things to remember when looking at any of David’s work is that he never left anything to chance: he wanted his paintings to be understood in a certain way and he planted enough visual clues for the contemporary viewer to “get it”.

We see Marat’s dead or dying body slumped in his bath in a position not unlike the dead Christ as he is being taken down from the cross. David makes his intentions clear from the start, this was no ordinary man and he is being elevated to a saint pretty much from the first. Marat’s face looks much younger than his 50 years and the skin disease is not much in evidence – this is a young man’s toned body, his serene face turned towards the viewer. The murderess Charlotte Corday is nowhere to be seen but she is there in two visual clues – the bloody knife and the letter Marat is still clutching in his hand. Corday uses the old calendar and addresses Marat in a roundabout way in marked contrast to David own address at the bottom of the wooden box: À Marat de David, addressing him as a friend, and, crucially, he dates it L’An Deux. This is Year Two of the Revolution which officially started 1 January 1793. Corday is unmasked in a way which would have been clearly understood at the time and David adds one more clue – the letter and banknote which is seen on the wooden box. Here is a different letter, from the widow of a Revolutionary asking for help with her children and the assignat on top suggests that Marat was about to make a charitable donation to her (as far as I know there is no evidence that Marat was indeed a charitable man). In David’s universe he was working in Spartan surroundings helping the poor while the Girondin sympathiser Charlotte Corday gained entrance under false pretence and murdered him in cold blood. A revolutionary martyr was thus visually created, not the only one in David’s work from this time but certainly the most famous.

Jacques Louis David managed to stay at the top of the art world through the Napoleonic era, not a small feat! He moved seamlessly from revolutionary to imperial subject under Napoleon Bonaparte for whom he created more unforgettable works such as the Coronation or Napoleon crossing the Alps, probably one of the most well-known images of the French Emperor.

It would take more space than this blog to discuss all David’s politically motivated paintings in detail but I hope you got a taste of what a political and artistic genius he really was.

History painting is anything but dull!