The tragic artist

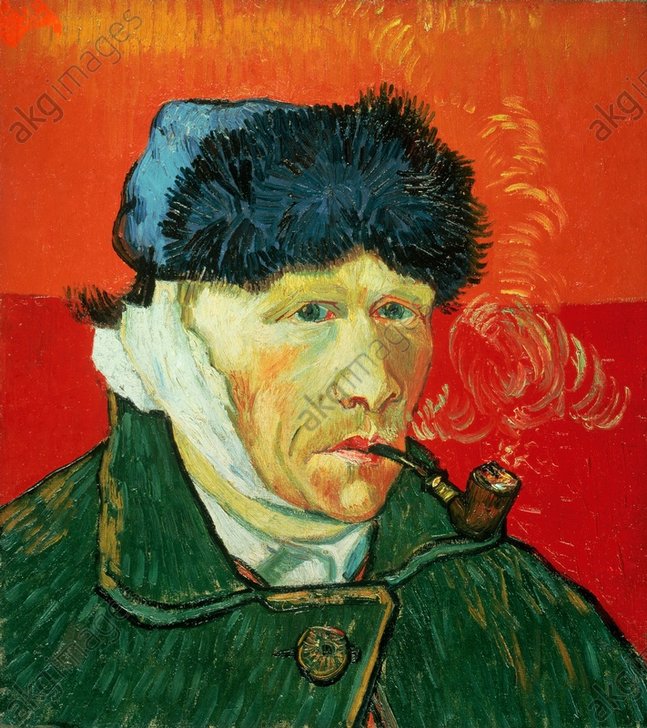

“Self-portrait with fur hat, bandaged ear and tobacco pipe”,

January 1889 © akg-images

125 years ago today, in the rented room in the Auberge Ravoux, Vincent van Gogh died of an infection caused by a bullet wound to his chest, aged 37. As Van Gogh’s fame subsequently grew, the drama and tragedy in his life became an important and inextricable part of the artworks themselves: the idea of the suffering artist, the penniless loner whose art was misunderstood during his lifetime and for whom acclaim came too late, the genius attempting to deal with mental health problems by committing his emotional state to canvas, before finally giving in and killing himself.

“Self-portrait in an attic”, circa 1813

© akg-images

I think it’s dangerous to fetishise this idea of the artist as tortured soul. Recent biographies of Van Gogh have tried to frame his mental health problems more solidly in reality, showing how frustrated Van Gogh became as he fought to gain the clarity he needed to work. It’s not even clear that Van Gogh meant to kill himself, or indeed that it was him that fired the shot: he didn’t own a gun and none was ever found. Although it’s essential to understand the man to be able to contextualise his work, should his life and death directly affect the artistic or financial value of the art he produced?

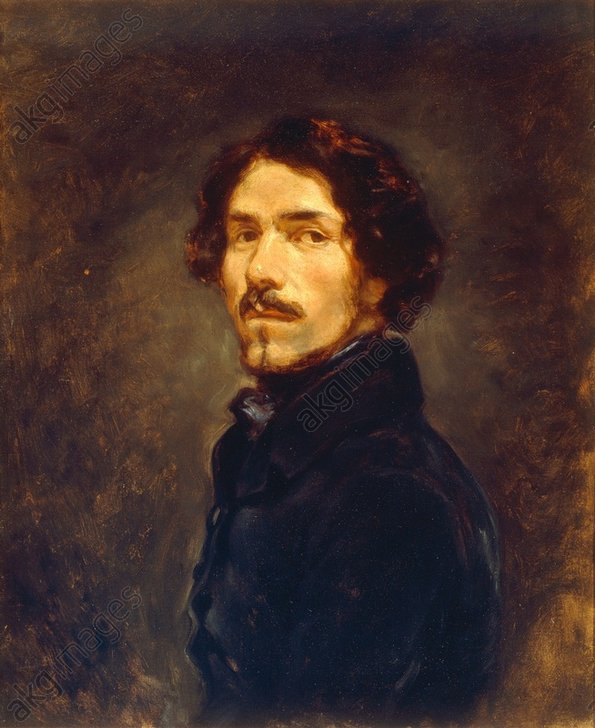

“Self-portrait”, circa 1840

© akg-images / Rabatti – Domingie

Although we’re familiar with the trope of the artist as a tortured loner, it’s actually barely two centuries old. It’s a product of the Romantic era, when artists like Byron and Delacroix became poster boys, as famous for their rebel hearts and smouldering looks as for their work. They were loners and nonconformists, and the image helped their sales. After Byron and Delacroix came the cult of the bohemian, the glamorous image of the artist in his garret about to starve to death (if the lack of heating doesn’t kill him first).

painting, 1620/21, by Anastasio Fontebuoni

© akg-images / Rabatti – Domingie

We have even taken this idea of the tragic genius and retroactively rewritten the lives of many of the great artists: Michelangelo is often portrayed at odds with society, by virtue of his genius and his homosexuality. It’s a nicely meaty dramatic conceit, because it’s not nearly as interesting to think of him as a highly talented artisan who was carefully trained and who sought out patrons to grant him significant commissions. Would someone railing against convention be given the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel to decorate? Similarly, people look at a painting by Caravaggio and try to join the dots between the art and the drama and violence in his biography, ignoring the equally important information about the provenance of the painting itself: who commissioned the work and why? Even in exile towards the end of his life, Caravaggio was still painting for his patron, Cardinal Scipione Borghese, and gaining commissions because he was a businessman with something to sell, not just an extremely talented painter.

“The workshop of the artist”, 1638

© akg-images / Erich Lessing

For every ‘tragic’ artist in history, there are tens of artists who were apprenticed, patronised, set up studios, apprenticed other artists, and died in relatively old age. Even Van Gogh received some training, as well as financial assistance, from a family member and fellow artist Anton Mauve. It may not be romantic, but many artists had studios where the master was more or less involved in the production of the art depending on how much money the client was willing to spend. Making art may involve genius and inspiration, but it also involves business nous and perspiration.

“Bohème-Café”, 1909

© akg-images

The drama and tragedy in Van Gogh’s life became an important and inextricable part of the value of the artworks themselves as they became more well-known following his death, but on this anniversary let’s look at the work and the life with our heads as well as our hearts: Van Gogh’s suffering didn’t make him a genius, his suffering informed and restricted the talent that was already there.